Spring 2025

Chancellor struggles to maintain headroom

On Wednesday 26th March 2025, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, presented her Spring Statement to Parliament. When the Chancellor finished her statement in the Commons, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) published updated forecasts for the UK.

As anticipated, the Chancellor’s package contained more than just updated fiscal forecasts from the OBR. She confirmed a series of spending decisions to offset a deterioration in the economic and fiscal outlook prepared by the OBR.

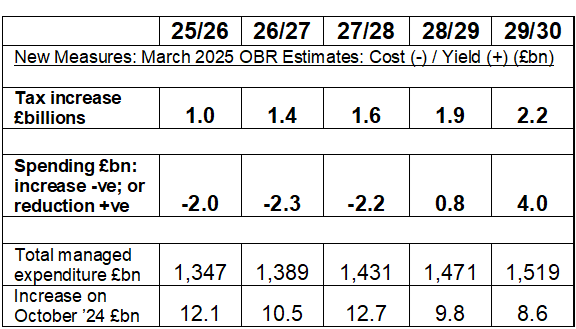

This became, therefore, a true fiscal event rather than, as the Chancellor might have hoped, a forecast and non-fiscal event! Albeit that the measures announced were each relatively small in the context of total managed expenditure of more than £1½ trillion (by the end of this decade: 2029-30).

The Chancellor’s statement reverses about one-third of the previous loosening of Government fiscal policy of £10bn for 2029-30 (relative to previous plans) that was put in place by her own Budget, last October. As this tightening is taking place from 2027-28 onwards, it should not significantly affect UK economic growth in the coming next two years, which means the implications for interest rates are also limited as well.

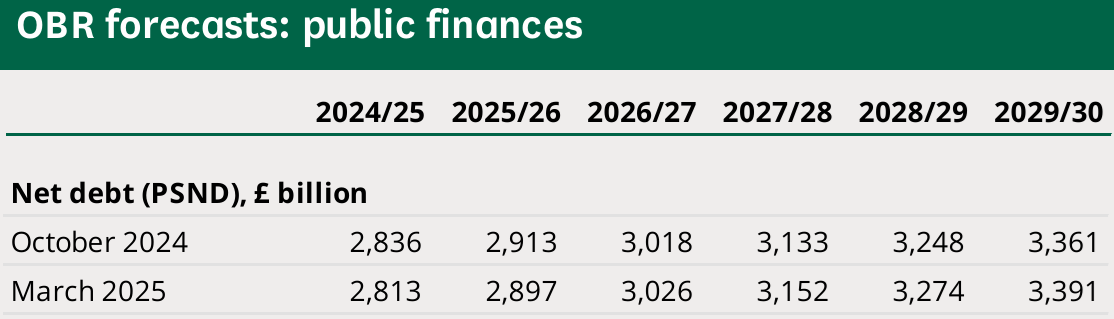

The profile of fiscal tightening announced is backloaded, that is to say there are substantial reductions in borrowing only in the final years of the OBR’s forecast – see table.

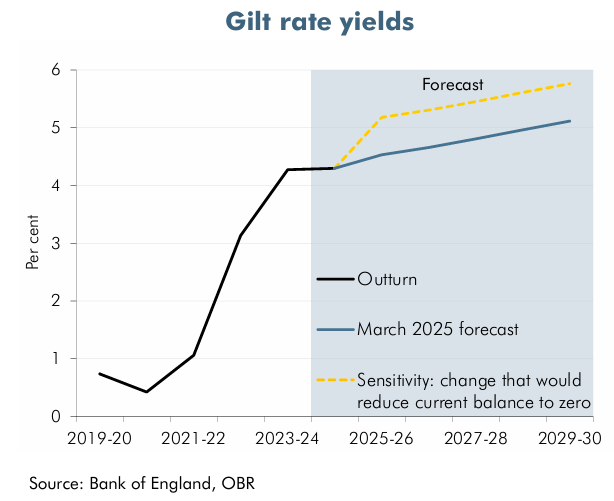

Hence, financial markets were fairly muted, with 10-year gilt yields moving little in reaction to the Spring Statement.

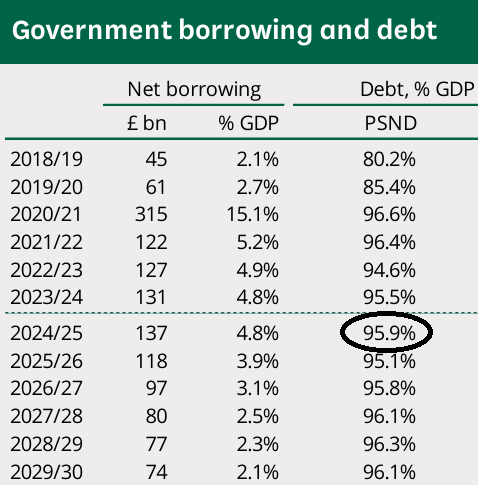

Before taking account of the Spring Statement, the forecast the OBR presented to the Chancellor halved the rate of GDP growth this year 2025 from 2 to 1 per cent, based on a continuing poor level of productivity; and showed the current budget in deficit by around £4 billion at the end of the decade.

Which is why government announced beforehand, principally, as a potentially significant modification in policy, proposed cuts to welfare and departmental current spending; with alteration of the residential planning system having already been mooted.

Last October, the government’s Budget spending policies added around £70 billion a year. Changes announced, new measures and a revision of the October Budget, were necessary and just enough to restore headroom against the Chancellor’s own tightly constraining “ironclad” rule: to run a current budget surplus balance (revenues minus day-to-day spending) in 2029-30. Even so, the OBR say the probability of this target being met is 54% . An interpretation indeed of a slim chance.

Effect of proposed new fiscal measures

The OBR’s revision of the outlook for the UK’s real GDP growth forecast of 2025, from five months ago, is because of an acknowledged weaker economy and rise in borrowing costs. Owing to domestic output deteriorating after mid-2024, with business and consumer confidence trending lower.

Unsurprisingly, various economists have expressed some concern about the outlook for the UK economy arising from the drag of higher payroll and business taxes (now +£38bn annually over the next five years), and a more uncertain global backdrop.

For example, a prominent independent forecaster projects that GDP in real terms will rise by 0.8% this year and 1.2% next year. Whereas the OBR, are more optimistic, keeping the average growth rate over the next five years unchanged at 1.7% a year, while now managing to share the general pessimism for 2025, with a revised significantly lower growth rate of 1%.

Since the October forecast, developments in outturn data and indicators of business, consumer and market sentiment have, on balance, been negative for the economic outlook.

The ONS has revised up the historical size of the UK workforce by ½ a million in 2024. It also revised up the level of real GDP by 0.8 per cent in mid-2024. But, the OBR say, real GDP growth largely stagnated over the second half of 2024 rather than continuing to grow, as the OBR had expected, in their October forecast. The net effect of these developments was that the measured level of productivity (output per hour worked) at the end of 2024 was 1.3 per cent lower than in the October forecast.

Around one-third of the lower growth this year reflects what appears to be structural weakness, derived from weak productivity. The remaining two-thirds is due to what appear to be cyclical, temporary, factors including higher interest rate expectations, increases in gas prices, and elevated uncertainty.

Since October 2024, european energy prices have risen again, and UK government bond yields are up by around ½ a percentage point.

The outlook is that wholesale gas prices are expected to peak at around 130 pence a therm in 2025, having risen sharply, which is around one third higher than that forecast last October.

Furthermore, the OBR say that historical revisions to Office for National Statistics (ONS) data suggested that more of the relatively meagre output growth seen since the pandemic has come from exceptionally strong growth in the size of the workforce, principally arising from migration, and less has come from growth in output per hour worked. Indeed, the latest ONS data imply that productivity of the UK workforce is actually falling over the course of last year, 2024.

To quote the OBR: ‘recent UK population, labour force, and output data do not provide a clear signal about domestic economic prospects’ or what this implies for the future productivity of the UK economy.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) - criticisms of reliability

Following criticisms of reliability of the ONS's labour force survey, for example, there is to be an external investigation into the effectiveness of the UK’s producer of official statistics. Internal work failed to fix issues identified for specific data sets, with a series of errors in important economic indicators.

The Bank of England's chief economist has raised concerns about ‘ongoing problems’, that have resulted in the Bank unable to ‘place much weight’ on ONS data for decision making on interest rate setting.

David Miles, macro-economist and one of three members of the OBR’s Budget Responsibility Committee, recently acknowledged that the OBR is widely seen as over-optimistic about the UK’s prospects, because the forecast for productivity growth remained higher than that of the BoE and other forecasters.

Richard Hughes, OBR chair, told a cross-party Treasury committee: ‘Ideally, we want a snapshot of where the economy just was, before we’re trying to figure out where it’s going over the next five years. Instead, at the moment we get an incomplete picture, from different points in time, from what we get from the ONS at the moment.’

Risks and uncertainties

Apart from those doubts, through poor base data, the OBR say that the outlook has also become much more uncertain with two specific geopolitical risks beginning to crystallise: upward political pressure on defence spending, issuing from the Ukraine war, and a tightening of global trade restrictions, arising from the Trump administration’s new U.S. tariff regime.

- High and volatile market expectations for Bank Rate and gilt yields continue to dramatically affect the UK’s fiscal outlook. Borrowing was projected to be over £13 billion higher in 2029-30 than in the October Budget. The most significant driver being higher forecast Bank Rate, gilt yields, and inflation, together increasing debt interest costs by amounts annually rising to £10 billion in 2029-30, relative to expectations in October 2024.

- The tax-to-GDP ratio is forecast to increase to a post-war high of nearly 38 per cent of GDP (2027-28). Partly driven by policies announced in the October Budget, including the increase of employer NICs and capital taxes. The OBR say the estimated yield from several of these measures remains ‘highly uncertain’.

- Departmental spending plans for the next three years are to be set in a Spending Review this coming summer. The forecast currently implies significant pressures on ‘unprotected’ departments, whose day-to-day budgets may need to be cut in real terms to accommodate other commitments that are ‘ring fenced’. A policy method questioned as unachieveable in reality.

- The Green Paper for a package of projected welfare savings, to restore some headroom against the Chancellor’s “ironclad” rule, are described by the OBR as ‘very uncertain’. Policy information on the direct fiscal effects was received late by the OBR, and without sufficient detail; certified only as a provisional estimate.

- The longer term fiscal outlook is described by the OBR as ‘very challenging’. Pressures from an ageing UK population are putting public finances on an increasingly unsustainable path. The OBR calculate that their baseline projection would require fiscal tightening of 1½ per cent of GDP per decade over the next 50 years to return debt to pre-pandemic levels.

Public finances

Following the October Budget, bond markets were surprised by the size of the increase in public borrowing, marked by a shift in interest rates across the forecast and at all maturities. Market expectations are now, on average, around a ¼ percentage point higher than was expected by the OBR in their October forecast.

UK 10-year gilt yields have risen by around ½ a percentage point since early October 2024.

The UK government requires financing, through issuing gilts across a variety of maturities, which has become increasingly sensitive to movements in interest rates, as a larger fraction of this total debt is subject to more frequent refinancing.

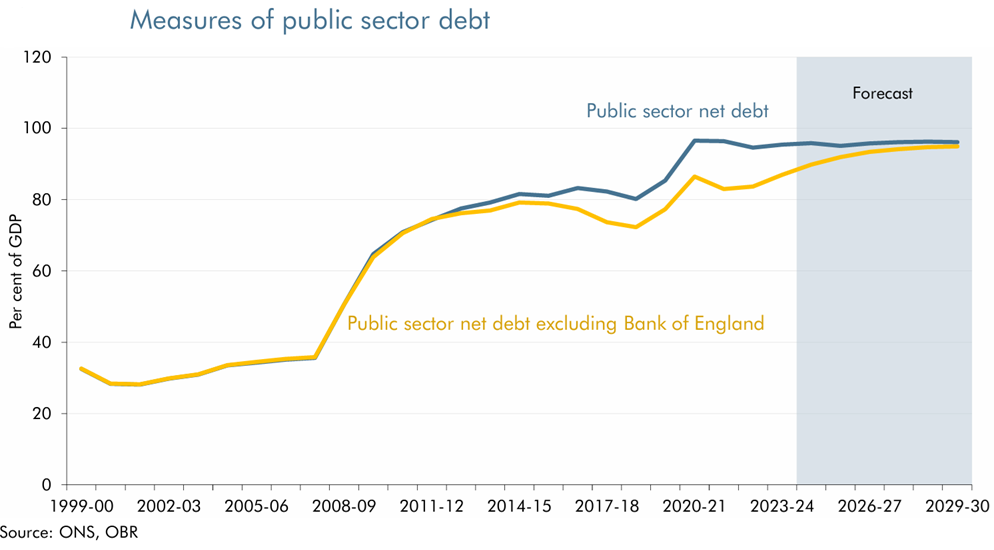

The stock of public debt has risen sharply from 28 per cent of GDP (Q1 2000) to 95½ per cent (Q1 2024), and is forecast to rise to over 96 per cent in 2029-30 or £3,391 billion (up +£30bn).

Bank Rate

A weaker UK economy, currently envisaged by the OBR and others, may eventually contribute to inflation falling back to target. This would enable the Bank of England to cut interest rates from 4.50% now to 4.00% or even 3.50%. Against this however, higher ‘sticky’ CPI inflation in this coming year would mean the Bank delaying any rate cutting in coming months, as a consequence of higher taxation and government borrowing.

Anthony Denny

5 April 2025