Autumn 2024

Budget delivers large increases in spending, tax, and borrowing

On Wednesday 30th October 2024, the incoming Government’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, presented the eagerly awaited, briefed and much anticipated Budget (this is the Labour Party’s first Budget for more than 14 years).

This Budget is described as ‘big’ by commentators, in terms of this Government’s plans for raising money and spending; and for showing that this Government will use borrowing throughout the coming five-years for spending on public services. With that proposed scale of Government spending described as ‘huge’ and certainly much greater than expected, by commentators or bond markets, at the time of the recent General Election. This should, temporarily, the OBR say, boost UK economic activity.

Government’s plans

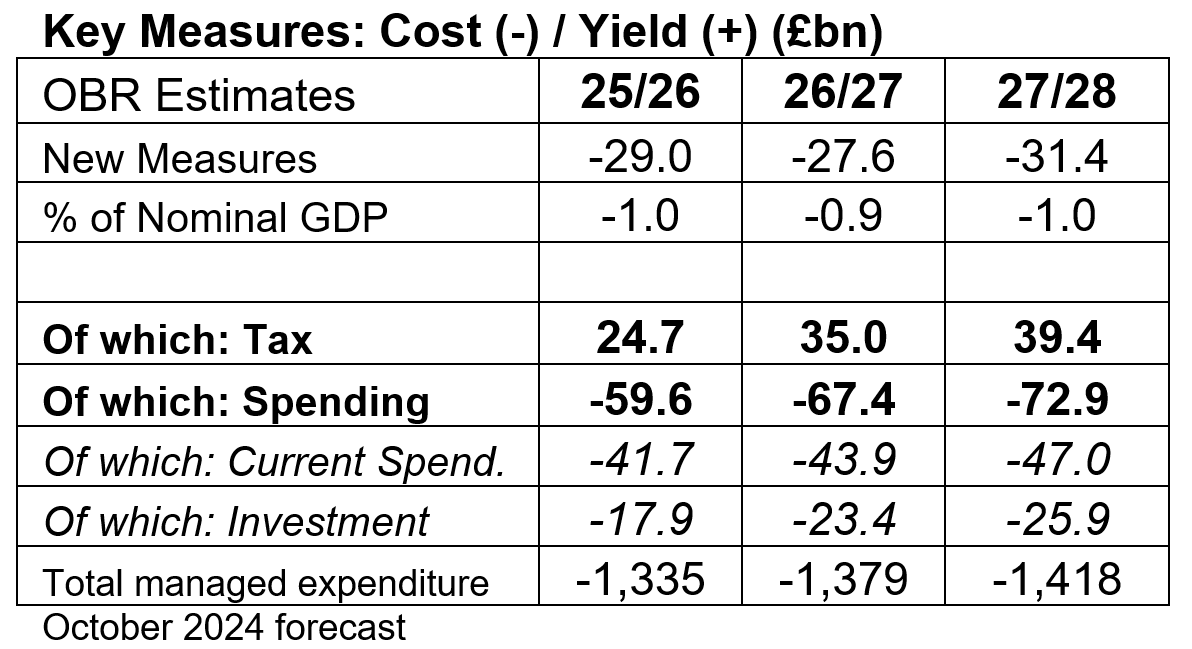

Against relatively unchanged economic circumstances since March, this Government’s Budget delivers a substantial increase in spending, taxation and borrowing. While the OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility) expects these policies to boost real GDP growth over the next couple of years, however, it also concluded that the policies would be a drag on growth over the following few years, because the fading boost to demand would be more than offset by two other influences:

- First, the drag on labour supply from higher employer national insurance contributions. The OBR assume this lowers real wages and profits, and workers and firms reduce labour supply and demand in response: reducing labour supply by around 50,000 people (on an average-hours equivalent basis). This is evenly split between a reduction in employment and a reduction in hours by those who stay in work.

- Second, the crowding out of business investment owing to higher public investment, because the OBR assume output is close to potential (in their pre-measures forecast – the forecast before the Budget’s measures).

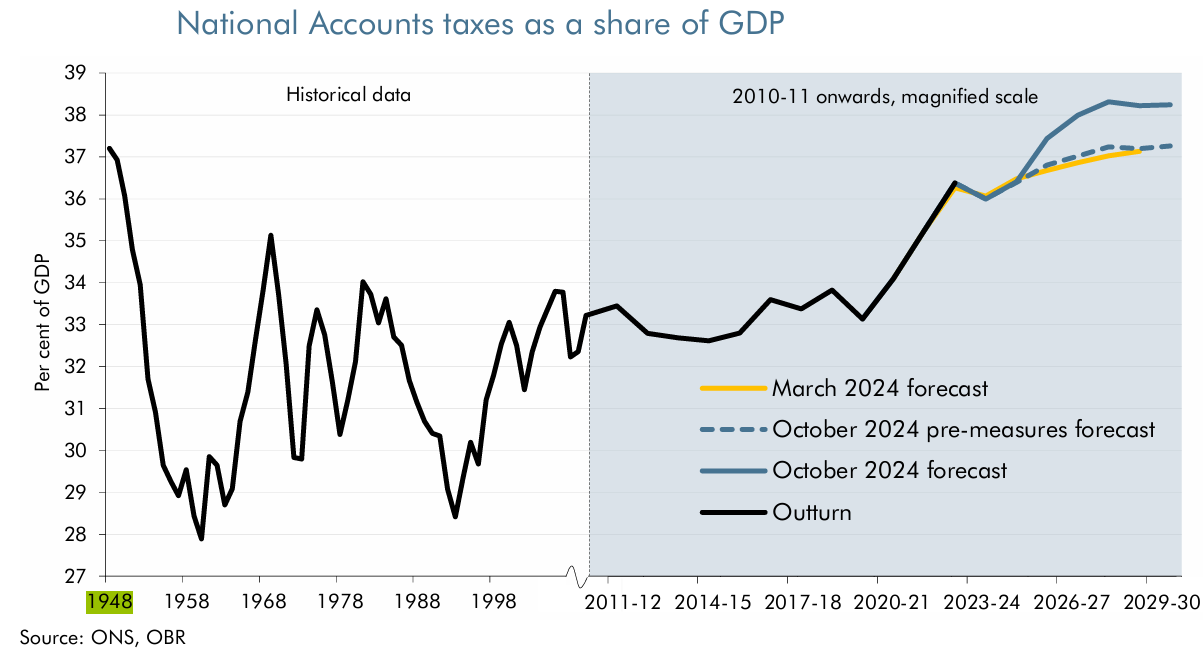

Just over half of proposed spending is funded through tax increases, raising around £36 billion annually, that push the state’s tax-take from the economy to a historic record 38 per cent of GDP in scale - the highest recorded level since 1948.

Relative to the plans of the previous Government, this Chancellor has added almost £70 billion per year to public spending over the next five years. With around two-thirds of this figure on day-to-day spending. Forecasting the state to be about 44 or 45 per cent of the UK economy (spending as a share of GDP) by the end of this decade: 5 percentage points higher than before the pandemic (around 2 percentage points higher than the level implied by the previous Government’s spending plans).

Richard Hughes, Chair, OBR’s Budget Responsibility Committee put it as follows:

‘In the 14 years since the OBR was established, it was only: George Osborne’s first Budget after the 2010 General Election; and Rishi Sunak’s mid-pandemic economic update in July 2020; that rival this Budget in terms of the overall change in the stance of fiscal policy.’

Having fallen from a pandemic peak of just over 53 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 to around 45 per cent of GDP last year, total public spending increases as a share of the economy this year (forecast to be 45.3 per cent of GDP in 2024-25 and 2025-26).

Public Finances

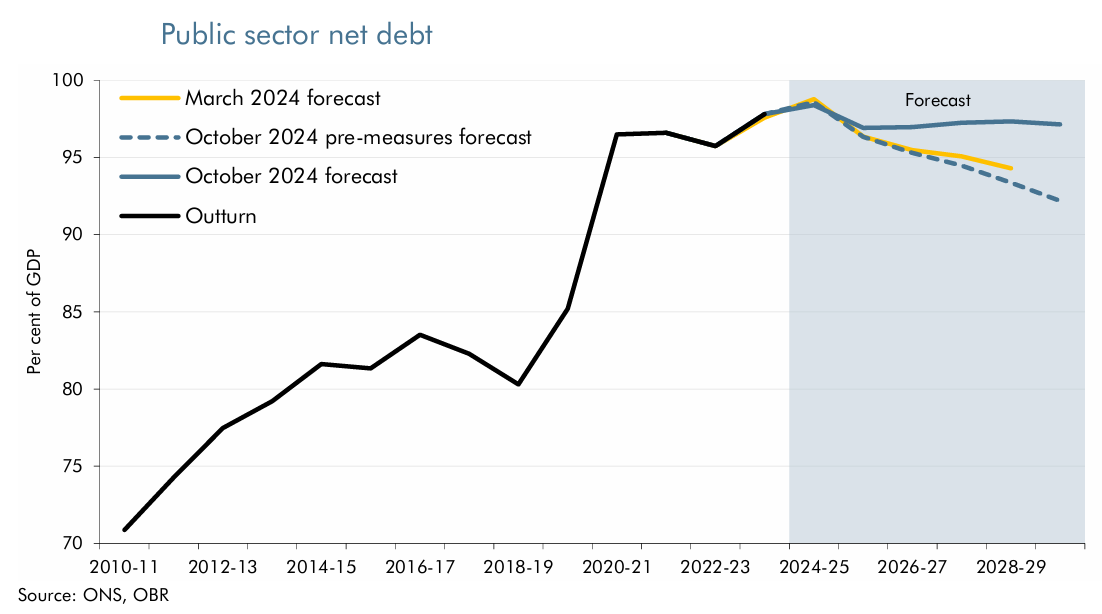

Public sector net debt forecast at £3 trillion by April 2027:

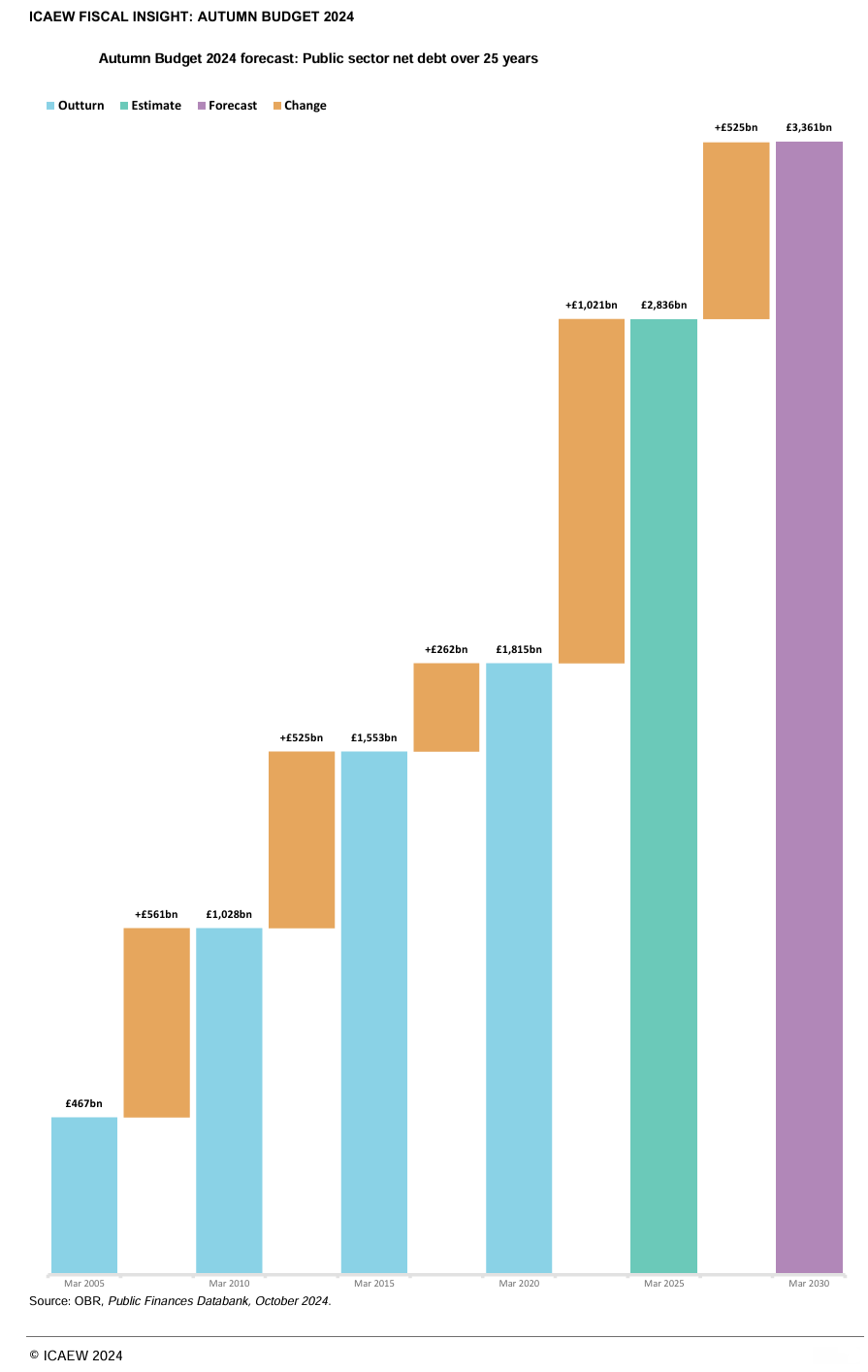

Public sector net debt (headline debt), largely the stock of past borrowing, increased from £404bn or around 31% of GDP, 20 years ago in March 2004, to an estimated £2,700bn, the OBR report, or 97.8% of GDP in March 2024. In monetary terms, a more than sixfold increase; in terms of GDP, more than threefold increase. See graph below:

Increasing headline debt over 25 years:

Headline debt was equivalent to 97.5% of GDP at the end of October 2024, at £2,792bn (96% of GDP at the end of October 2023), and predicted by the OBR, to remain post Budget, at around 97% of GDP for the lifetime of this parliament, forecast by the OBR to be in March 2030: public sector net debt, £3,361bn.

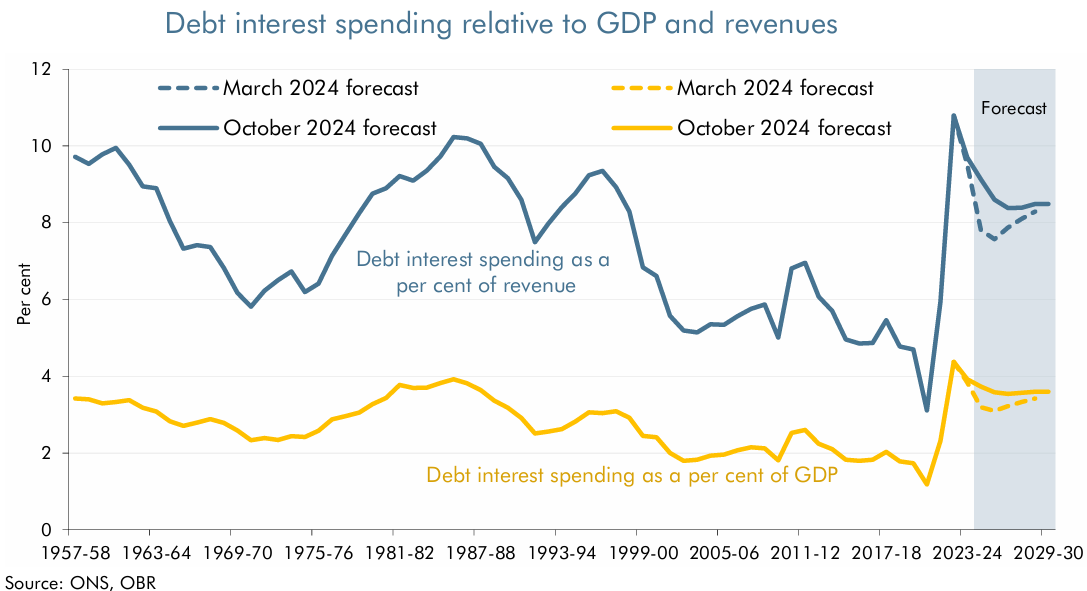

'Back To The Future' for debt-interest spending from revenue

Debt interest costs (outturn for 2023-24: £106bn), as a proportion of revenue, are now greater than 10% and at a level higher than the 1960s or 1980s (see graph above) - now forecast to exceed £100 billion a year in each of the next five years. Projected by the OBR to be greater than a £120 billion a year by the end of this decade (2029-30).

This follows a decade and a half of weak UK economic performance since the financial crisis, the turmoil of a global pandemic and an energy price shock, ensuing from the war over Ukraine.

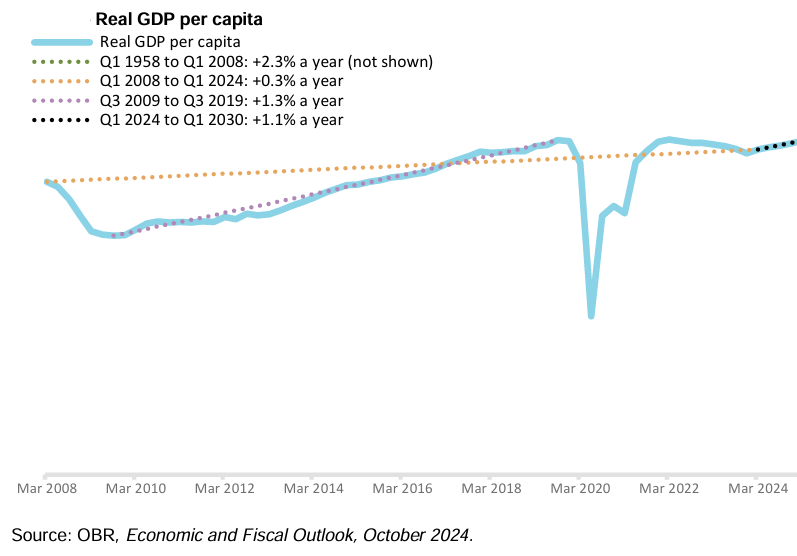

For productivity, in this period, (GDP per capita) there have been seven successive quarters of negative growth per head of population. (see graph below)

Challenges for the state include a projected 25% increase in the number of UK pensioners over the next 20 years, contrasting with a 9% rise in the working age population over this same period. If public finances stay on their current path, the OBR have predicted that headline debt of the state would rise to be around three times the size of GDP in the next fifty years.

Government borrowing

The other half thereabouts of the increase in spending will be met through ‘looser fiscal policy’. That is total government borrowing falling more slowly, and to be around one per cent of GDP or £32 billion higher a year over the five-year forecast period. Data released subsequent to the Budget demonstrates the degree of reliance on borrowing: taxes and other receipts fell short of public spending by £97bn in the seven months to 31 October (£15bn more than budgeted), the third-highest cumulative total for October on record.

GDP forecasts and Bank Rate

Since much of the current spending begins immediately, GDP growth may be up to ½ percentage points stronger in 2025 than the rate of 1½% that some forecasters have been predicting.

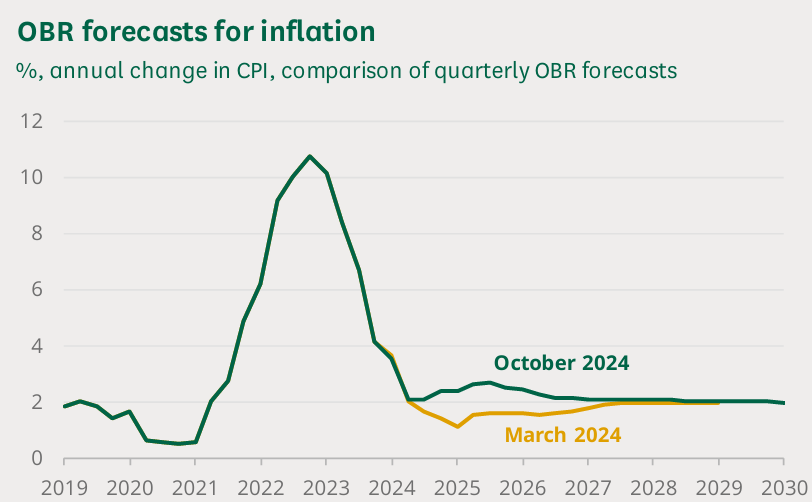

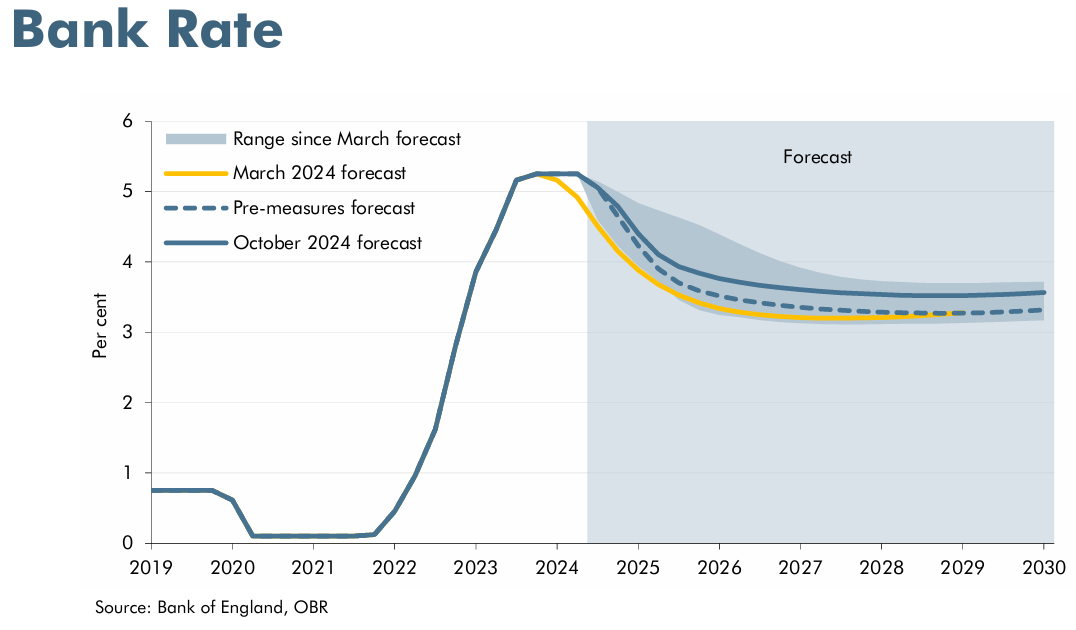

Moreover, as the rise in public investment adds to demand, inflation may also be higher than otherwise, meaning the Bank of England (BoE) might cut interest rates more slowly, although Bank Rate may still eventually fall to a forecast of 3.5%.

Inflation expectations

While cutting interest rates from 5% to 4.75% on 7 November 2024 (down 0.25 percentage points), the BoE implied that the Budget means interest rates will continue to fall only gradually.

The OBR say that having stagnated last year, the UK economy is expected to grow by just over 1 per cent this year, rising to 2 per cent in 2025, before falling to around 1½ per cent (slightly below its estimated potential growth rate of 1⅔ per cent), over the remainder of the five-year forecast.

OBR expectations for growth in 2025 and 2026 are more optimistic than those from most other forecasters, including the Bank of England, which in August 2024 forecast GDP growth of 1.0% in 2025 and 1.3% in 2026.

Historic record tax-take expected

While overall, this Labour Budget is historically (since 1948) one of the biggest tax-raising Budgets on record, whether this can kick-start a period of faster economic growth in the general economy, as a whole, as opposed to the state sector in part - time will only tell.

Bond markets were surprised by the size of the Budget’s increase in public borrowing. The rise in 10-year gilt yields from 4.24% before the Chancellor’s speech to 4.37% afterward implied this, but obviously not nearly to the same extent as occurred after the Truss administration’s announcement of their notorious ‘mini budget’.

The sell-off in gilts (on the day of the Budget), commentators suggest, was due to higher term premia reflecting market concerns about the rise in the future supply of gilts, worries about the fiscal picture presented, and would lead the BoE to be more cautious about the pace of interest rate cuts.

Indeed, it was pointed out by commentators, that the policy of slowing the reduction in borrowing, has raised Bank and gilt rates by a ¼ percentage point across the forecast and at all maturities. Higher interest accounts for some of the crowding out of business investment by raising the cost of capital.

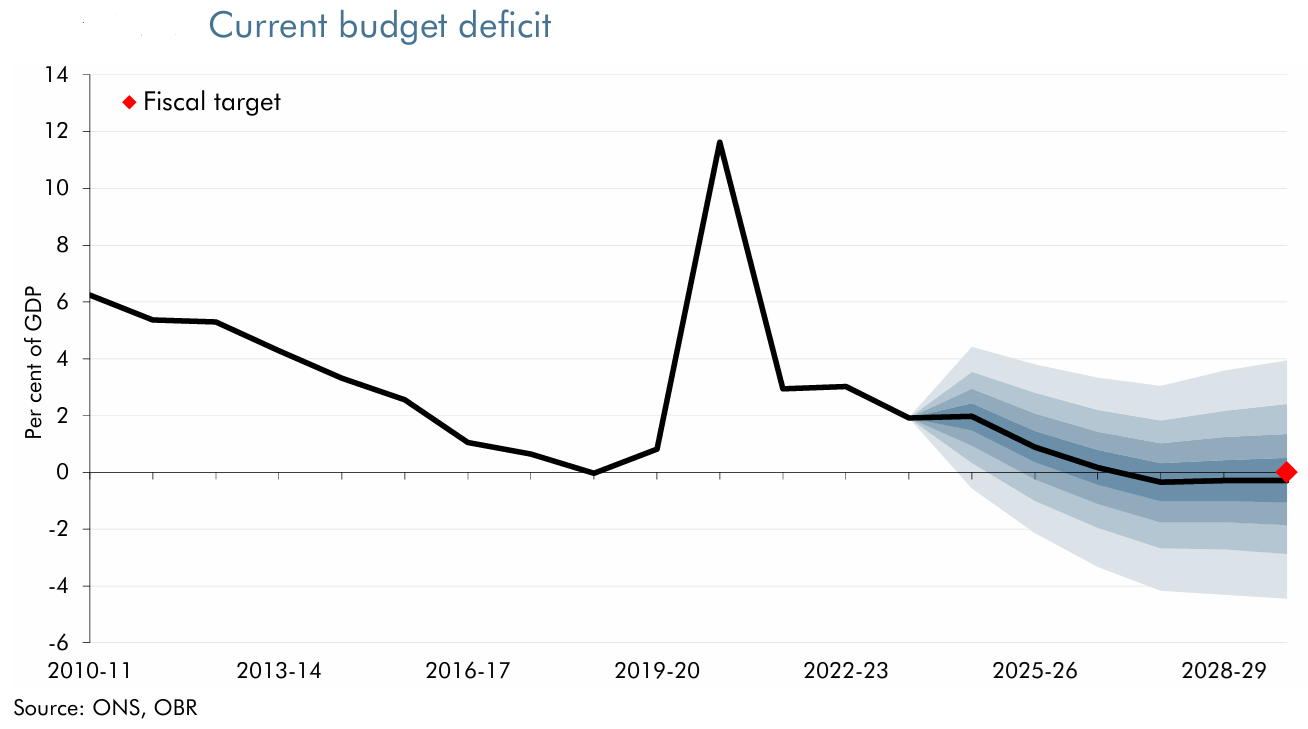

Furthermore, looking at the newly defined three-year target of the current budget rule, of which there is headroom of less than £10bn; any further increase in day-to-day public spending would need to be funded by yet higher levels of taxation.

Current budget forecast is close to the wire - see graph below for proximity to fiscal target:

Anthony Denny

27 November 2024