Autumn 2020

Coronavirus pandemic delivers largest peacetime economic shock

On Wednesday 25th November 2020 the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, presented to Parliament a ‘Spending Review’ confined to the year ahead 2021/22, not the usual three, together with the Office for Budget Responsibility’s economic and fiscal outlook, November 2020: the latest update of forecasts for the UK economy in general and Government’s spending and borrowing.

This is the first forecast of the new Chairman of the OBR, appointed in October 2020, Richard Hughes.

In their March 2020 report for the Budget, despite the political pandemonium of Brexit of the previous year, the OBR said that the near-term economic outlook at the time of closing their forecast appeared little changed. That, of course, was before the spread of the coronavirus disease. The pandemic has since become, the OBR say, the most important determinant of our economic and fiscal prospects.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged from eastern China in December 2019. The first reported confirmed case of infection in the UK was on 31 January 2020, which with some irony was the date the UK ceased to be a Member State of the European Union with the Withdrawal Agreement coming into force.

Within ten months, successful trials of vaccines undergoing testing produced encouraging news that: “… takes us another step closer to the time when we can use vaccines to bring an end to the devastation caused by SARS-CoV-2”; “…findings show that we have an effective vaccine that will save many lives”; and “excitingly, we’ve found that one of our dosing regimens may be around 90% effective and if this dosing regime is used, more people could be vaccinated with planned vaccine supply”, according to the Oxford professors engaged in the development of the vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, titled AZD1222.

It is made from a genetically changed, weakened version of a common cold virus.

The UK Government has pre-ordered 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine, and AstraZeneca say they will make three billion doses for the world next year (2021).

Assumption of availablilty of vaccination critical to OBR scenarios

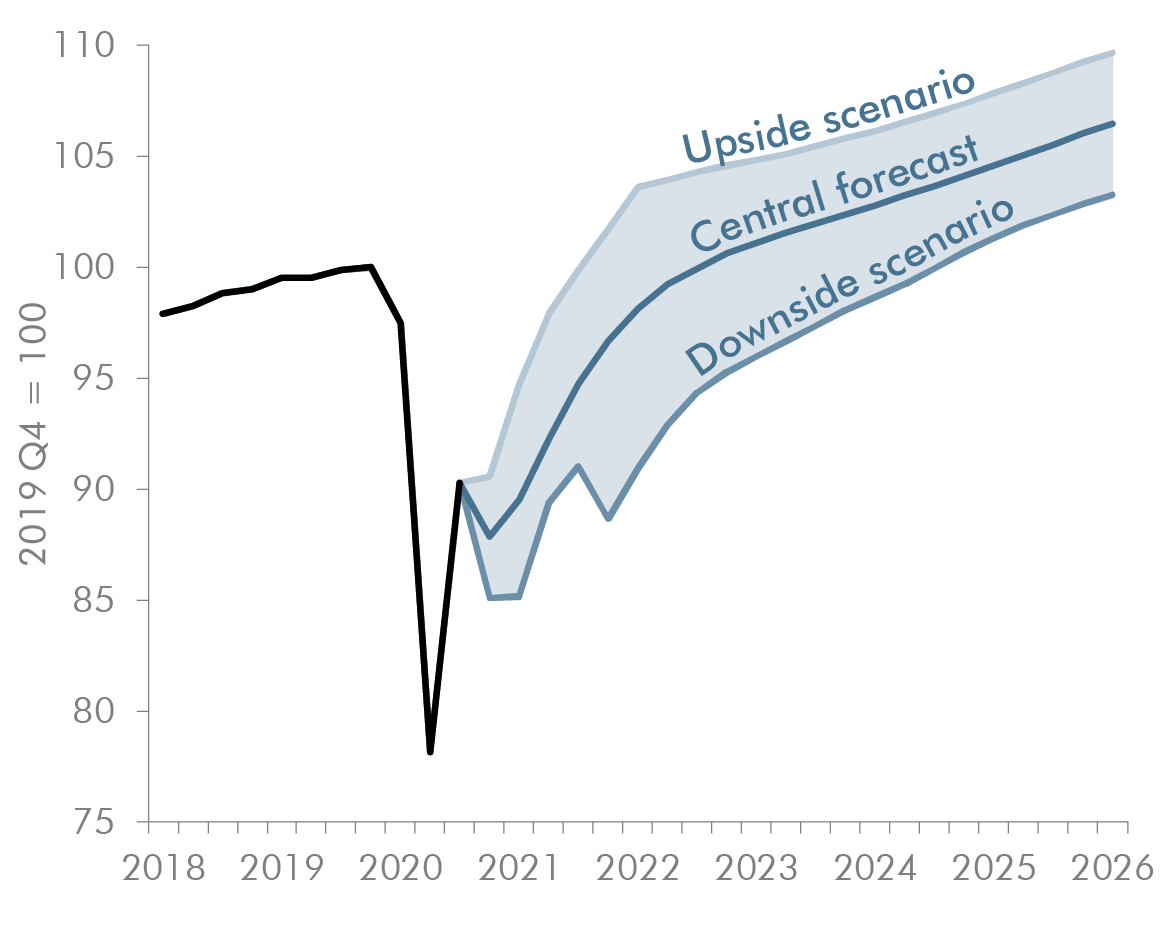

While the OBR’s report contains ‘central’ forecasts, the continuing uncertainty of present circumstances suggests, they say, that reliance on any single prediction or forecast, would be misleading. Several scenarios are presented by the OBR, giving the range of likely outcomes, being dependent on:

(1) assumptions about the stringency of pandemic restrictions,

(2) availability of vaccination for the general public; and

(3) successful conclusion of an agreement for trading with the European Union.

In these circumstances, the value of a single ‘central’ forecast is limited.

Without a trading agreement, from January 2021 the UK will trade with EU countries on World Trade Organisation terms, which provides a basic floor for world trade. The OBR say this is likely to reduce the level of UK output (GDP) by 1½% after five years, owing to temporary short-term disruption, if there is no smooth transition to a ‘typical’ free trade agreement. Consequently, borrowing, the OBR estimate, would increase by around £10 billion.

Understandably, the Treasury could not provide clarity to the OBR on the ultimate outcome of negotiations and the OBR based their forecasting on the assumption that a deal is reached.

The economic risk of no-deal may be partially additive to existing conditions. Yet the scale of output lost this year owing to disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic is “obviously much greater”, concedes the OBR, and dwarfing in comparison.

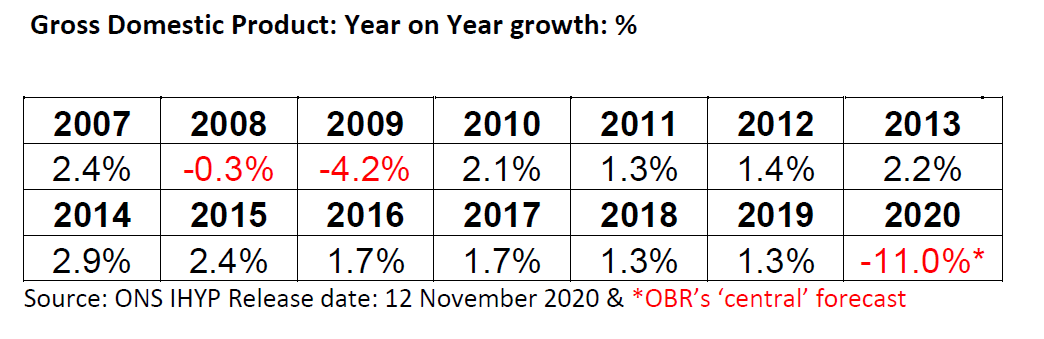

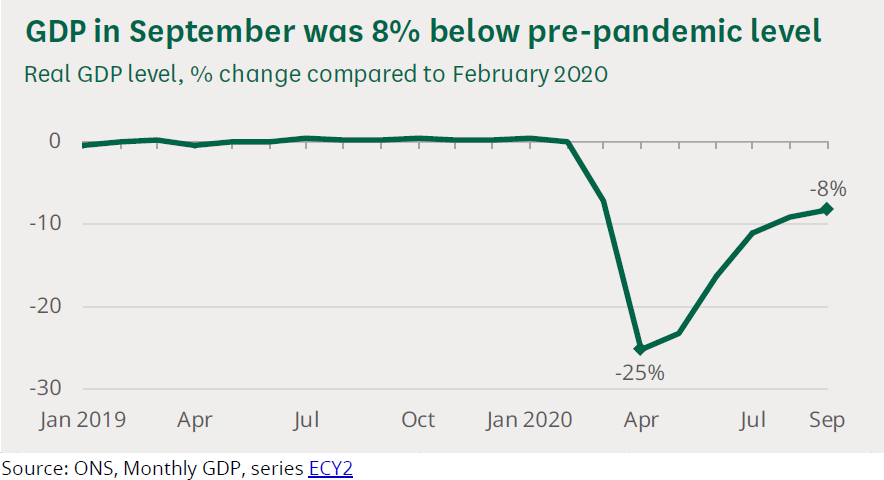

The economic conclusion of the coronavirus pandemic is that there has been the largest peacetime shock to the global economy in modern history. Output lost this year will likely result in a contraction of UK GDP in 2020 by approximately 11%.

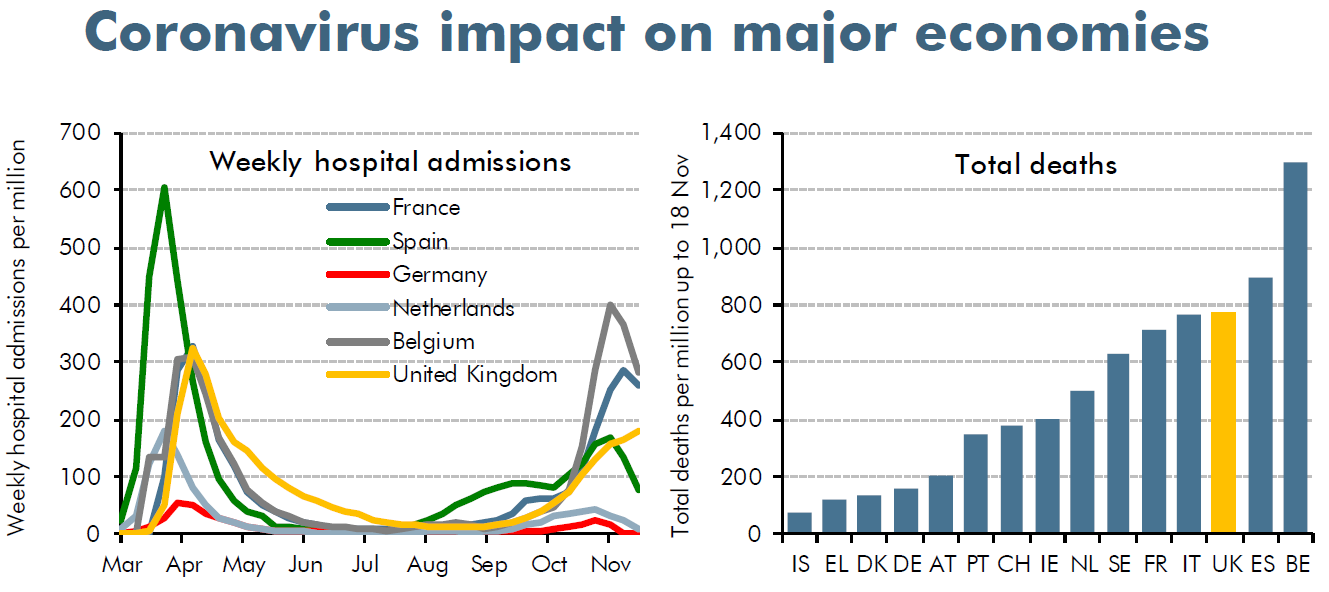

Of advanced economies, during the period March to November 2020, the UK has experienced one of the highest rates of hospital admissions and deaths. Only Spain and Belgium have fared worse statistically in terms of cases per million.

The UK introduced more stringent restrictions, but later than many other European countries, and maintained them for longer, leading to a fall in output by more than one fifth (>20%), the sharpest contraction of any major advanced economy other than Spain.

Economic impact of pandemic on UK economy

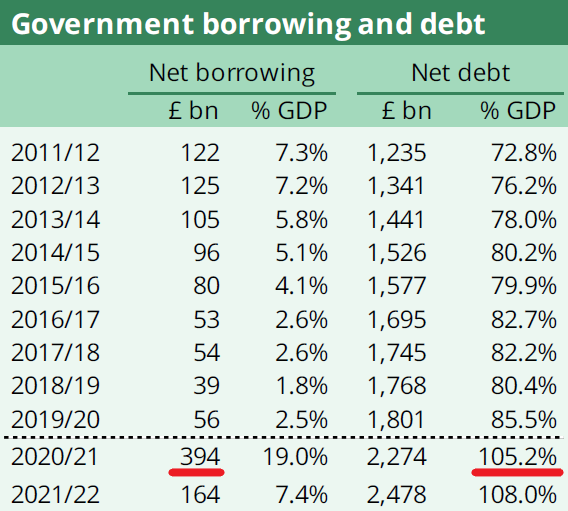

The effect on the UK’s public finances is profound. The OBR’s ‘central’ forecast envisages a deficit this year, between Government receipts and spending, near to £400 billion (or in scale, about one fifth of UK GDP). Leading to Net Debt of over 100% of GDP (in cash terms, GDP was £2,214 billion in 2019).

OBR’s upside and downside scenarios and ‘central’ forecast

An upside scenario from the OBR, paints a rosier picture, with the vaccine widely available in the spring, and a ‘rapid return to relative normality by the end of next year’. In their upside scenario, output rebounds by the end of next year and is back on track after five years, with no long-term effects: hence the medium-term economic impact of the pandemic is negligible in this scenario – which may be overly optimistic for the UK?

The OBR’s ‘central’ forecast suggests that effective vaccination of the general public occurs in the latter half of 2021, permitting the eventual return of normality. However, the OBR have pointed out the limited value of their ‘central’ forecast.

Whereas their downside scenario, envisages the continued spread of the coronavirus disease, with waves of transmission requiring periodic national lockdowns, and the continued risk of infection seeing lasting changes in the conduct of life. Emphasising the dependency of the UK economy on effective vaccination. Before the development of vaccines this downside scenario was possibly the more realistic, taking account of recent experience.

Unlike previous economic recessions, the OBR say, the Government’s policy response has been the principle determining factor of cost to the exchequer.

Of the £339 billion upward revision to the previously expected borrowing level of £55 billion before the pandemic, that is between the OBR’s March and November ‘central’ forecasts, roughly three quarters is because of additional spending, particularly on the health service and furlough schemes. The remainder is owing to lower economic activity and therefore lower tax receipts.

This all leaves the Government borrowing one pound in every three that it is spending. To quote the OBR, the public finances are: ‘…significantly adrift from any definition of balance…’.

Forecast 2020-21: public sector current receipts of £771bn as a proportion of total managed expenditure of £1,165bn is equal to approximately 66%; resulting in public sector net borrowing of £394bn, 34% of total spending.

The statutory Charter for Budget Responsibility requires the OBR to judge whether the Government has a greater than 50% chance of meeting specified fiscal targets under current policy. These were proposed by Chancellor Philip Hammond and approved by Parliament, January 2017. In their report the OBR confirm all three legislated borrowing and debt targets are “missed by wide margins” in each of their predicted scenarios.

To put this in context, among the 35 advanced economies and G7, the UK has seen the second largest increase in Government spending (second only to Canada and by some margin in front of the USA, France and Germany) - 10 times higher than was borrowed in 2018-19 (a mere £39 billion) and more than twice the level of peak UK Government borrowing (£158 billion) in 2009-10, following the financial crisis.

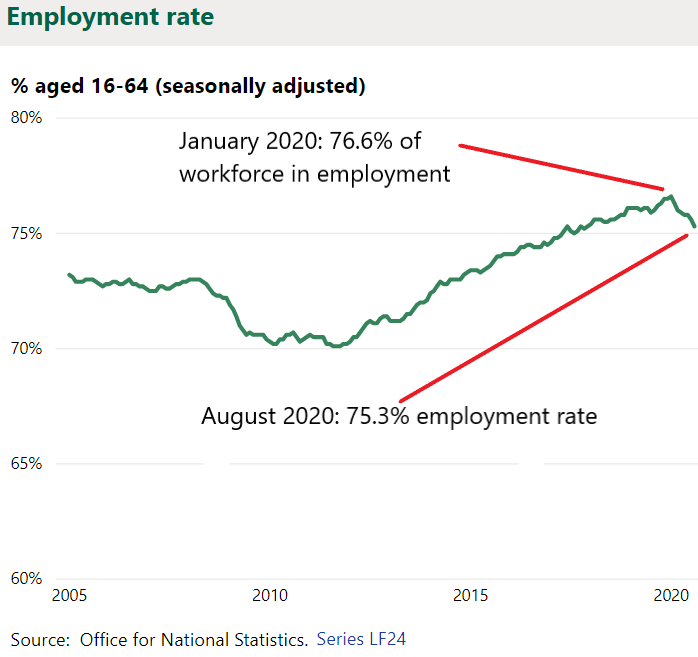

Labour Market

The Office for National Statistics estimates that 32.51 million people were in employment in July-September 2020, an employment rate of 75.3% of those aged between 16 and 64 years. To recap, as a benchmark, the labour market ended 2019 with the highest employment rate of 76.5% or 32.99m people and joint-lowest unemployment rate of 3.8%, since comparable records began in 1971.

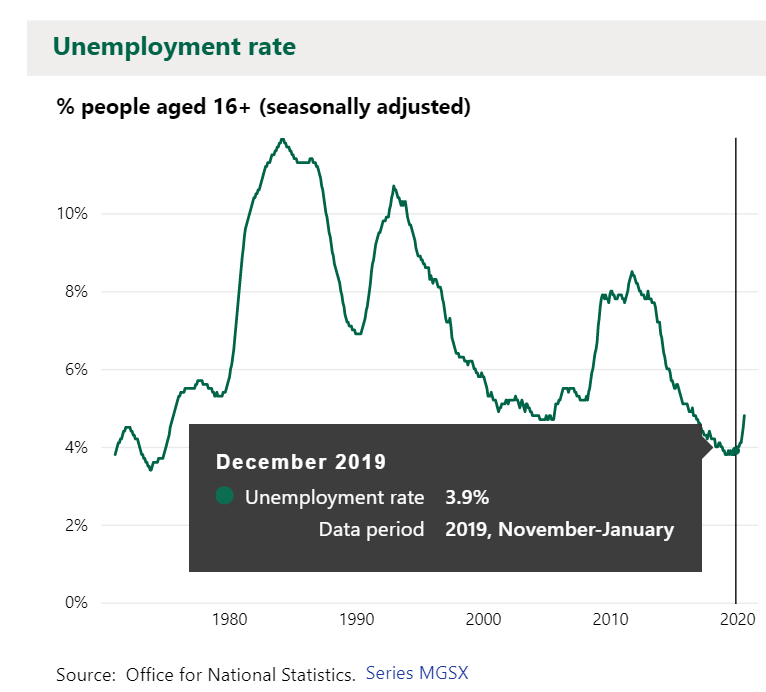

There were 1.62 million unemployed people in the UK in July-September 2020, an increase of 318,000 from the year before. The proportion of the economically active population who are unemployed is estimated by the Office for National Statistics as 4.8% increasing by 0.9 percentage points on the year. The rate peaked at 8.5% in late 2011, following the financial crisis. Also for comparison, the rate was 11.9% in April 1984 and 10.7% in January 1993, see graph.

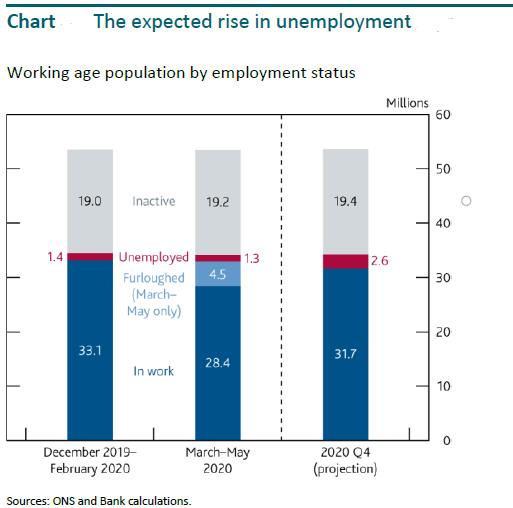

Currently, the OBR’s macroeconomic modelling predicts a ‘significant rise in unemployment’ and the future unemployment rate to be next year between 6% and 11%, translating to between 2 million to 3½ million unemployed. The Treasury’s October 2020 survey of independent forecasts estimates an average rate of 7% by the end of 2021 – about 2 to 2½ million people.

Although the pandemic has not yet resulted in the expected flow from employment to unemployment, the Bank of England’s modelling similarly corresponds with the OBR and other forecasters predicting a projected unemployment rate of around 7¾%, inferring more than 2½ million people out of work and searching for jobs towards the end of next year.

Government borrowing and ‘quantitative easing’

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has cut the Bank Rate twice since March 2020, reducing it from 0.75% to 0.1%, and a negative Bank Rate is being contemplated.

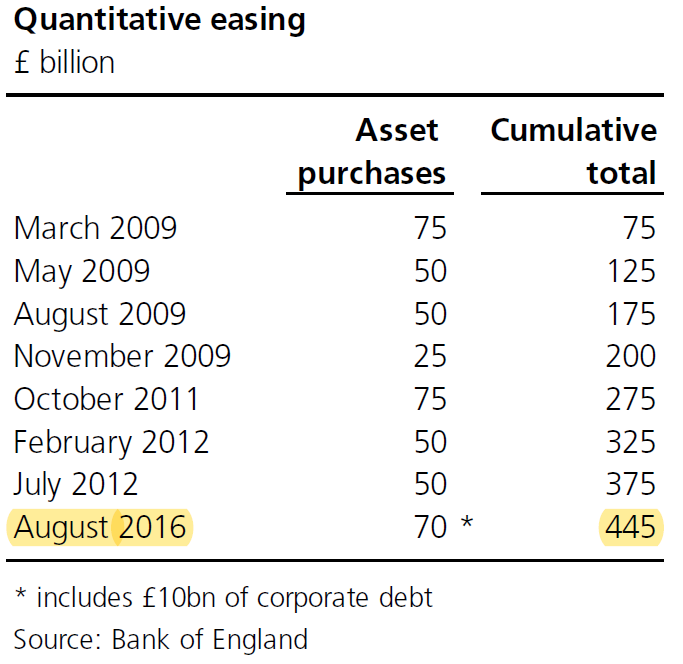

The Bank of England say ‘quantitative easing’ is a tool to inject money directly into the economy by creating money, the aim is to increase spending in the economy. The programme stood at £445 billion in March 2020 and £450 billion has been created to deal with the pandemic (approx. one fifth of GDP).

Following the additional programme announced in November 2020, the authorised limit for the Asset Purchase Facility Fund (APF) will rise to £895bn. The first programme had an upper limit set at £150bn, introduced in March 2009 by Chancellor, Alistair Darling, in the wake of the financial crisis.

However, as the Bank of England itself has concluded, the effect is to increase the price of other assets, as well as bonds, such as shares and property.

Another effect of the expansion programme of money creation has been to significantly increase the sensitivity of the public finances to future changes in interest rates by reducing the maturity of debt issued. Also, according to the OBR, the UK now has an increased reliance on foreign investors (38% of gilts) and, hence, risk to changes in investor sentiment in future.

While the intention of the programme in 2009 implemented in response to the financial crisis might have been that the ‘very large build-up of commercial bank reserves at the Bank of England’ would be reversible; that possibility now appears most unlikely within the foreseeable future.

Anthony Denny

3 December 2020