|

On

Wednesday 22nd November 2017 the Chancellor Philip Hammond presented to

Parliament the Conservative Government’s fourth Budget, his second and the

‘first Autumn Budget’. This is under a new Parliamentary schedule, intended

to end tax announcements being made twice each year. The idea is to announce

tax changes well in advance of the tax year.

The

Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) also published their updated

forecast, which they have been doing since 2010.

GDP growth slightly subdued, but steady

In March this year, UK consumer confidence appeared un-dented by the EU

referendum result for Brexit, with UK economic growth during the second half

of 2016 continuing unabated, arising from the strongest annual expansion of

consumer spending since 2004.

This year, 2017, GDP growth has been slightly subdued, but steady, primarily

owing to a slower rate of growth in consumer spending.

In fairness, even though this may be described as a ‘noticeable slowdown’

from those higher growth rates seen in recent years, the latest quarterly

GDP growth in the third quarter of 2017 is similar to that reported for the

first two quarters of the year.

The cause may well be that, on average, real earnings have continued

to fall. Yet earnings are increasing above inflation for the lowest-paid

employees, who have benefited from the National Living Wage. The main

beneficiaries being part-time workers, in contrast to weaker earnings,

between 2016 and 2017, for workers on middle levels of pay.

The Treasury’s survey of forecasters indicates GDP growth for 2017 of around

1.6%. At the March 2017 Budget the OBR had forecast growth in 2017 of 2%,

now revised down by 0.5 percentage points. The OBR expect a steady fourth

quarter, reinforcing performance consistent with growth of 1.5% for 2017

as

a whole.

Last year, the OBR had expected growth to slow, mainly owing to higher

inflation and their continuing concerns over weaker business investment

which it assumed depressed future productivity growth.

Even so

growth of the economy has been slightly weaker this year than they

originally anticipated in March 2017, now closer to their muted Autumn 2016

predictions. The OBR believed then that there would be ‘significant’

downward pressure on growth in 2017 and 2018. The OBR's concerns revolved around

two main judgements which underpin their economic forecasting:

1.

Firstly, uncertainty regarding future trade and migration policies leading

businesses to defer investment, exacerbated by price-inflation squeezing

consumer spending, partially mitigated by stronger export trade.

2.

Secondly, that potential growth in productivity is weaker, owing to weaker

investment, while acknowledging that this link is not well understood.

As it has

transpired this year, weaker sterling appears to have had the predicted

effect of inflating import prices, in turn pushing up consumer price

inflation, which then has squeezed household incomes.

The

Sterling Exchange Rate Index (SERI) measuring sterling’s value against a

‘basket’ of currencies is just over 26% below its January 2007 peak level.

But on average the pound was up nearly 6% from November 2016 and the third

successive month the year on year increase has been positive. The value of

the pound against the dollar had fallen sharply since the EU Referendum,

from $1.48 on 23 June 2016 to around $1.35 at the start of December 2017.

At the

start of December, the Euro was valued at around €1.14 per £1, which

compares with a daily all-time low of €1.02 in December 2008 and a launch

rate of €1.48 in December 1998.

Weaker sterling has also helped export growth, although this is reported as

only partially offsetting the effect of unexpectedly strong import growth.

UK productivity

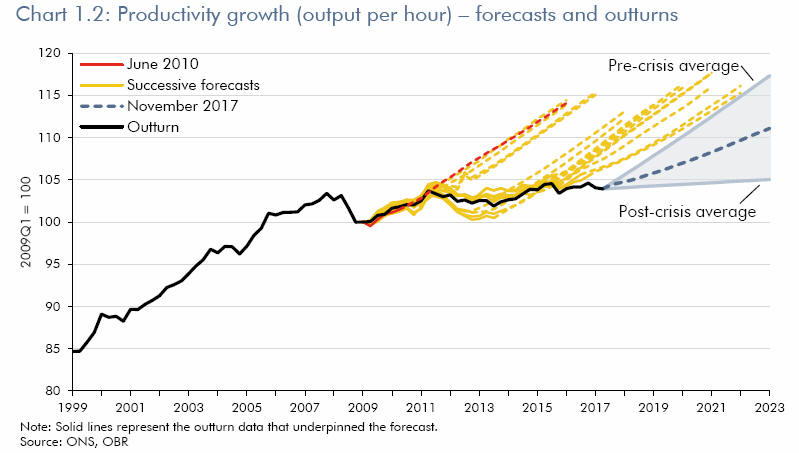

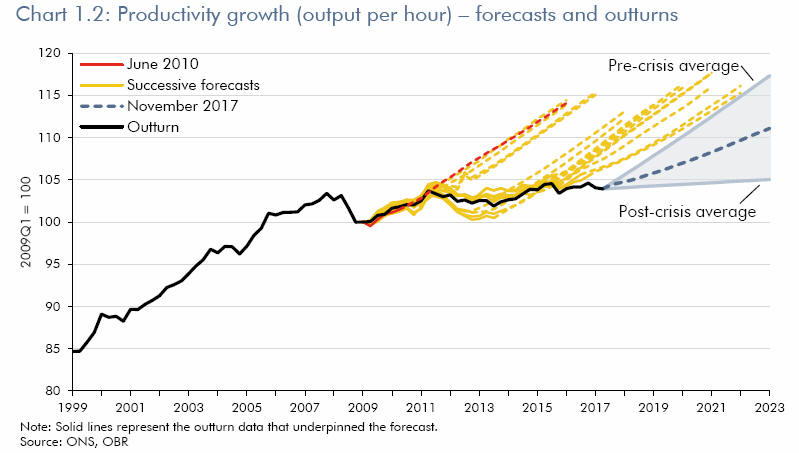

The OBR have now significantly revised their opinion about the prospects for

UK productivity, which changed markedly in the wake of the 2008/09 Crash,

leading to a revision of economic growth throughout their forecast.

Although the outcome has been that economic growth this year has not

diverged greatly from the OBR’s March forecast, the breakdown of the

relationship between employment and productivity has shown a much greater

divergence.

Over the last three quarters of 2017 employment has risen by nearly one

quarter of a million people at a rate that is twice as fast as expected, but

average hours worked per person in the UK have been close to flat rather

than falling as expected.

Similarly, just before the 2008/09 recession, GDP and GDP per head (in real,

inflation-adjusted, terms) peaked in 2008. During the recovery GDP surpassed

this level in mid-2013 and now (Autumn 2017) 9.7% above the pre-recession

peak. Yet, if you adjust for population growth the gain in GDP is much

lower, with GDP per head only 2.4% above its pre-recession level of a decade

earlier.

The pattern of unexpectedly strong employment growth and unexpectedly weak

productivity growth has been a consistent and constant feature of economic

forecasts since the Crash.

This inescapable fact has led the OBR to revise assumptions about the

potential size of the UK economy based on historic rates of potential

productivity growth.

Productivity growth has been much weaker since the Crash than for decades

beforehand. Output per hour has risen by just 0.2% each year since 2008,

compared to an average of 2.1% a year over the preceding 35 years.

Any judgement about potential hours worked in an economy reflects judgements

about population size of those active and employed, and the number of hours

worked on average.

To the OBR it now seems sensible, some might say realistic, to take account

of weaker UK productivity. Review of this critical assumption has taken some

time in coming.

UK gross domestic product - outturn

Gross domestic product (GDP), the monetary value of all the finished goods

and services produced, has had unbroken growth for 19 consecutive quarters,

the latest revised official statistics from the ONS estimate growth to be

1.8% in 2016.

The

latest updated statistics for growth (or fall) in GDP reported by the ONS,

for the last decade are:

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

2.4% |

-0.5% |

-4.2% |

1.7% |

1.5% |

1.5% |

2.1% |

3.1% |

2.3% |

Source ONS: IHYP November 2017

As an indicator of confidence and predictor of performance, the Purchasing

Managers’ Index was 54.5 this time last year. It has kept stable, above the

‘magic 50’ level, for fifteen consecutive months following the EU

referendum. It is now 53.8 (Dec’ 17), having previously shown the fastest

pace of growth in business activity for six months.

In 2016, the service sector accounted for 79% of economic output, the

production sector 14%, construction 6% and agriculture 1%. Growth in the

dominant services sector (retail, financial, leisure) accounts for 84% of

workforce jobs, but has slowed this year.

In contrast, manufacturing output has been growing at an average annual rate

of 2.2% in the past four quarters, seemingly benefiting from an increase in

export orders.

Recently, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) survey suggests that

UK manufacturers are reporting the strongest order books since 1988.

Apparently net trade has contributed modestly to overall growth in the first

half of 2017, contrary to the OBR’s expectation. Exports have been boosted

by a strengthening global economy, and in particular from the Eurozone.

GDP by Expenditure: household consumption is the largest element of

expenditure across the economy, accounting for 63% of the total in 2016.

Government consumption accounted for 19% and investment 16%.

The Bank of

England believes Brexit-related uncertainty is weighing on investment. The

overall level of investment in the economy is only slightly higher (2%)

in

2017 compared with 2007, the pre-recession peak level.

In contrast with the UK’s latterly subdued economic growth, the world

economy has strengthened during 2017.

The IMF

noted, in its recent appraisal of prospects for future world economic

growth, that the Eurozone, which has struggled to establish a sustained

recovery since the global financial crisis has been on an upward trend,

with GDP 2.5% higher in Q3 2017 compared with a year before, and the

highest growth rate for a decade. Growth in the US has also picked up this

year.

The IMF has said that improved growth

of the world economy is “notable because it is broad-based”.

Forecast for world GDP growth

On 28 November the OECD raised its 2018 GDP growth forecast for the

UK to 1.2% from 1.0% in the previous September forecasts, (their 2017 UK

growth forecast is at 1.5%).

Inflation and monetary policy

Headline inflation has tipped just over 3%. Although, the CPI measure

averaged 2.6% in 2013 and 1.5% in 2014, it was very low for most of 2015, at

near zero, before picking up again. That historic fall in inflation was

largely owing to the fall in the oil price and lower food prices. These have

since increased.

The fall in the value of the pound since late 2015 and following the EU

referendum in June 2016 has caused higher import prices, which probably have

been passed onto consumers.

One of the key drivers of inflation is the price of food, around half of

food and drink consumed in the UK is imported.

Bank of England research suggests price pressures faced by producers have

eased in recent months. The Bank forecasts inflation to ease to around 2% to

2½% next year, relieving the squeeze on households’ finances.

The

Bank's MPC can look through the fact inflation is above 2%, if there is

the belief the situation is temporary. However, owing to the decade-long

stagnation in UK productivity, the most important factor governing the

growth potential of an economy, the MPC revised their view that this

factor is likely to return to the pre-crisis average of 2% per year.

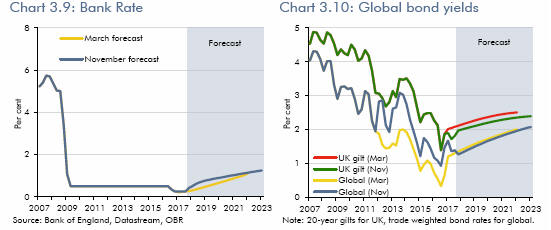

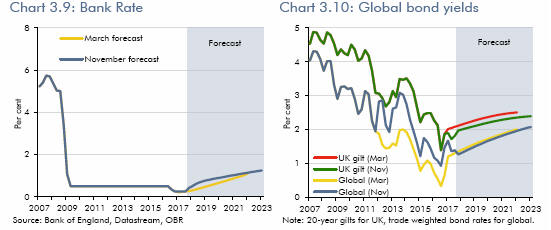

Higher inflation was the cue to raise

interest rates for the first time

since 2007. Reversing the previous policy decision to reduce rates following

the EU referendum which had held the Bank Rate at 0.5% for seven years prior

to August 2016.

Consumers and households have been somewhat squeezed by inflation, average

wage growth adjusted for inflation (July-September 2017) was 0.6% lower than

a year before. Remarkably though, wage growth remains weak despite

unemployment being at its lowest rate since 1975 and near-record UK

employment rates, confounding economists’ expectations.

Labour market

The UK labour market continues to surprise following the 2011 dip. From then

on, UK employment has grown relentlessly from 29 million; 32.06 million

people in the UK were recorded in work in the three months to October 2017,

just over 75% of people aged from 16 to 64 in the UK, an increase of over 3

million people in the workforce since 2011.

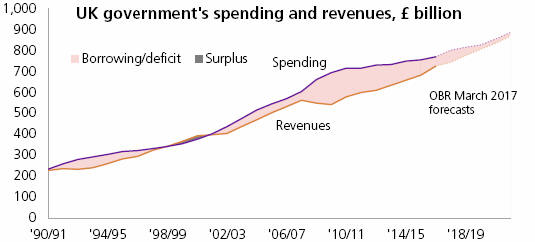

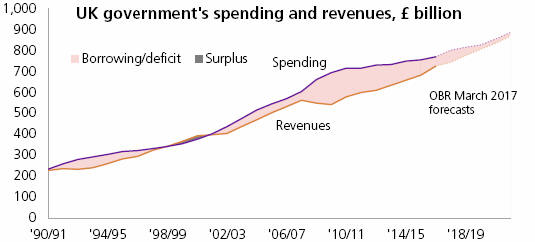

Public finances

Once

again, public finances have been performing much better than the OBR have

expected. The revised estimate of annual public sector borrowing for 2017/18

is £50 billion - previously forecast as £58 billion.

Government spending in excess of tax and other revenues is commonly known as

‘the deficit’. Government borrowing for the deficit has fallen considerably

since the massive borrowing during the financial crisis, from a peak of £153

billion in 2009/10 to £46 billion in 2016/17. As an indicator of size this

is just over 2% of GDP and similar in scale to the level of borrowing before

the 2007-2008 financial crisis - the historical average from the mid-1970s

to 2007/8 is 2.6%; post-war average to date is 2.4%.

The principal reason the OBR have revised their expectation of future growth

is owing to a downward revision of potential productivity growth. If UK

productivity does not improve then pressure may mount on future Government

borrowing.

The OBR say Government remains on course to hit the looser targets set for

borrowing and debt in 2020-21, but with less room for manoeuvre. The

longer-term objective of “balancing the Budget”, which was the ambition of

the 2010 Coalition Government to achieve in 2015/16, now looks more

challenging.

But, they are on their way to getting there. Government borrowed less in the

first half of 2017/18 than during the first half of 2016/17.

Public sector net debt

In March the OBR expected public sector net debt (PSND), the total stock of

Government debt, to peak at nearly 89% of GDP this year, 2017-18. It is

still considered that debt will peak during the fiscal year, but at the

slightly lower figure of 87% GDP.

As a comparison, the 2010 emergency budget predicted the gargantuan figure

of 70% GDP, and Alistair Darling, Chancellor in the last Labour government,

had planned for it to rise to no more than 75% GDP, from the pre-crisis base

of 35% GDP.

Alternatively, another comparison might be the recorded public-sector net

debt after World War 2 (1946/47), which was then a truly whopping 259% of

GDP!

The

Treasury's lucky black cat, Gladstone, the photogenic resident Chief Mouser

of HM Treasury at Whitehall.

Anthony Denny

December 2017

|